University of Southern Mississippi History Project

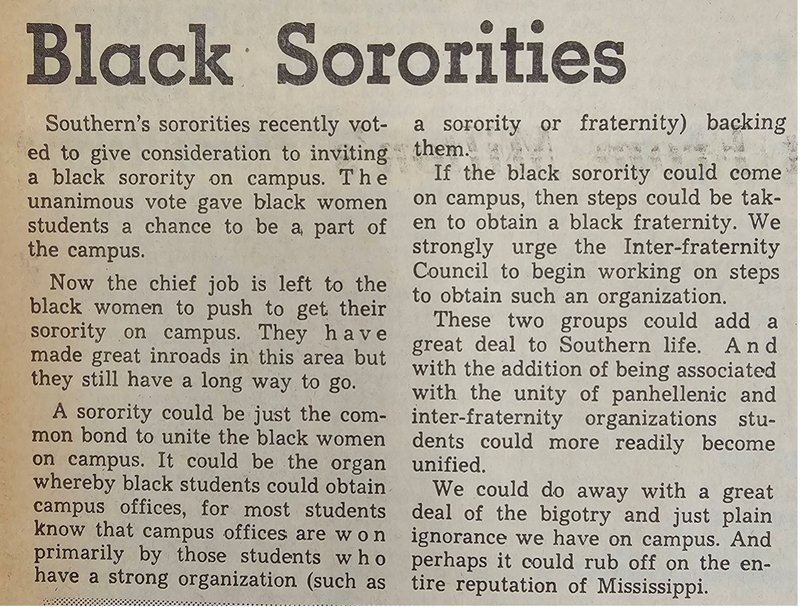

Image 1. Anonymous article against racial integration of Panhellenic sororities (“Southern Sororities Face Black Issue,” Student Printz, 17 November 1970, Special Collections in McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi, 2.)

Panhellenic Sororities: Facing an Exclusionary Past, Striving for a more Inclusive Future

Kyle Simpson

The University of Southern Mississippi formally desegregated in 1965, when Gwendolyn Armstrong and Raylawni Branch enrolled at the school. Not only were Armstrong and Branch the first Black students to attend the university, but they were also the first Black women to attend one of Mississippi’s formerly white-only universities. Unlike the violent reaction to James Meredith’s enrollment at the University of Mississippi in 1962, Armstong and Branch’s integration of USM was peaceful. Yet, while their integration of the school was peaceful, there were certainly racial tensions on campus.

Five years after Armstrong and Branch integrated USM, gender and racial tensions led to anxieties from Panhellenic sororities on campus. Those tensions heightened in 1970, when USM’s white sororities were set to vote on whether to integrate their chapters, or to allow Black sororities on campus. In the lead-up to that vote, an anonymous article was published in the Student Printz, wherein the author argues against racial integration of white sororities, dramatically stating, “Those who live in Panhellenic held their breath … for fear that Black women will be coming through rush.” (Image 1). The author argues against integration based on unspecific references to chapters’ efforts to integrate causing issues on other campuses. They also write off integration of white sororities as efforts that would only be seen as “tokenism.”

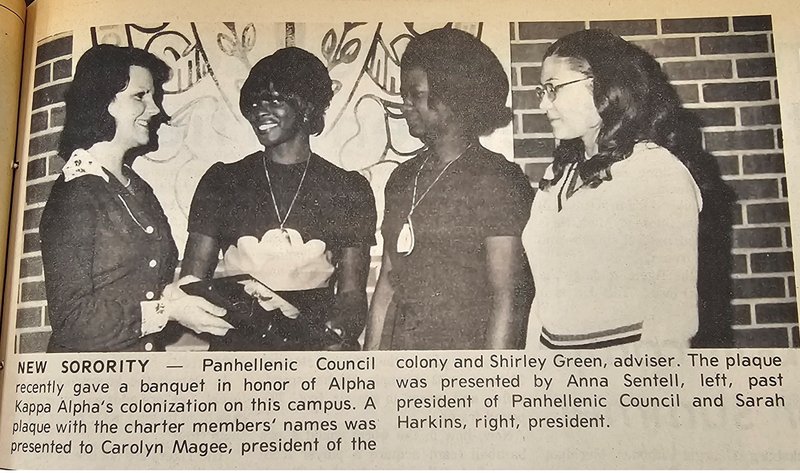

The vote was a unanimous agreement among white sororities to allow Black sororities on campus, rather than desegregate their chapters. Following the vote, another anonymous article was published in the Student Printz that praised the decision (Image 2). Despite the result being a rejection of integrating sororities, the author claims that allowing Black sororities will unify the students at USM and, somehow, “… [D]o away with a great deal of the bigotry and just plain ignorance we have on campus.” The implication being that if Black students no longer tried to integrate white Panhellenic organizations, racist reactions from white students would diminish.

Image 2. Anonymous article praising vote that allowed a Black sorority on campus but did not allow racial integration of white sororities (“Black Sororities,” Student Printz, 8 December 1970, Special Collections in McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi, 2.)

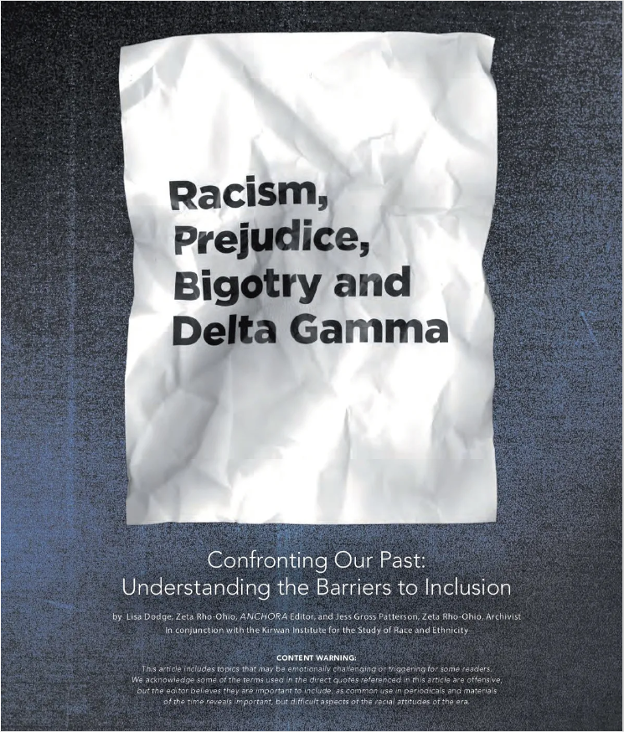

Whether or not Black Greek organizations coming to USM’s campus unified the student body in any way, they did indeed open chapters on campus. In 1975, Alpha Kappa Alpha became the first Black sorority and Greek organization on campus (Image 3). There are now chapters for all four sororities and five fraternities of the Divine Nine—historically Black Greek organizations governed by the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC) that formed in response to the racially exclusionary practices of white Greek organizations—at USM. Today, the member organizations of the North American Interfraternity Conference (IFC), National Panhellenic Conference (NPC), and NPCH all officially practice non-discriminatory practices; however, historically white and historically Black fraternities and sororities are still largely de facto segregated.

Image 3. Photograph of banquet honoring Alpha Kappa Alpha being chartered (“New Sorority,” photograph, Student Printz, 20 March 1975, Special Collections in McCain Library and Archives, The University of Southern Mississippi, 3.)

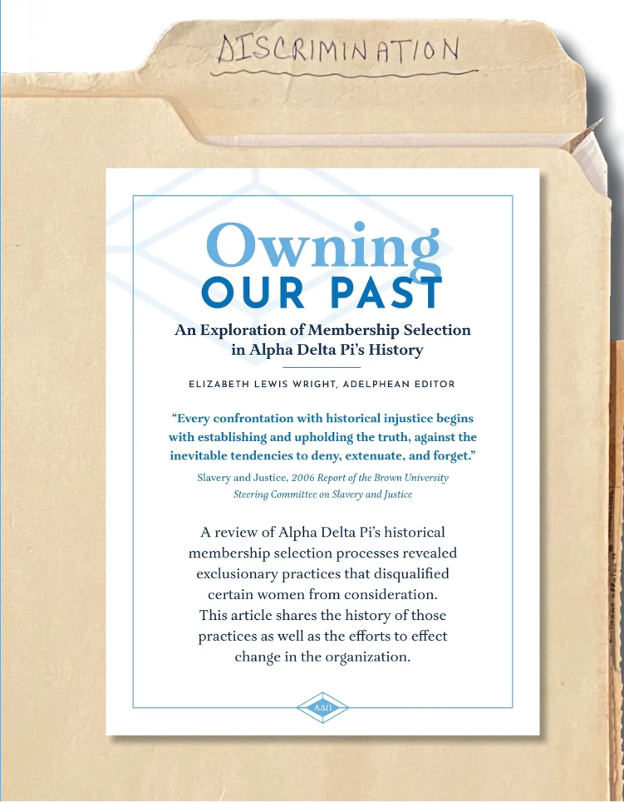

Recently, there has been a more active, or at least more visible, effort on the NPC’s part to be more inclusive. The organization’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) webpage offers a list of steps it has taken to be more inclusive, most of which were not started until after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Some member organizations of the NPC have taken the further step of releasing and confronting archival evidence of their past racially exclusionary and discriminatory practices. The national headquarters of the Alpha Delta Pi (founded in Macon, Georgia in 1851, when Black people were enslaved in the state) and Delta Gamma (founded in Oxford, Mississippi in 1873, during a time of white supremacist backlash to Reconstruction in the state) sororities have both published such projects in their quarterly journals, The Adelphian (“Owning Our Past: An Exploration of Membership Selection in Alpha Delta Pi’s History”) and Anchora (“Confronting Our Past: Understanding the Barriers to Inclusion”), respectively. Delta Gamma’s effort, “Confronting Our Past,” is notable, given that it was published before the summer of 2020 (though 2019 is still quite late, considering the organization’s then 146-year history).

Image 4. Article cover from Anchora issue highlighting Delta Gamma’s participation in racist exclusion and other discriminatory practices (Lisa Dodge and Jess Gross Patterson, “Confronting Our Past: Understanding the Barriers to Inclusion,” Anchora (Winter 2019): 12-21, http://digital.watkinsprinting.com/publication/?m=3174&i=647238&p=1&pre=1&ver=html5.)

Image 5. Article cover for The Adelphian issue highlighting Alpha Delta Pi’s participation in racist exclusion and other discriminatory practices (Elizabeth Lewis Wright, “Owning Our Past: An Exploration of Membership Selection in Alpha Delta Pi’s History,” The Adelphean 124, no. 4 (Summer 2020): 6-19, https://editiondigital.net/publication/?m=17352&i=665883&p=6&ver=html5.)

Locally, the College Panhellenic Council, which governs the NPC-affiliated historically white sororities on USM’s campus, has also taken recent steps to become more inclusive. On their DEI Initiatives webpage, the CPC lists several initiatives it has created to accomplish greater inclusivity. In 2022, the CPC created a new position, the Vice President of Inclusion and Wellness whose job is to spearhead the CPC’s DEI initiatives. The first VP of Wellness and Inclusion, and incoming CPC President, Paige Fellows, agreed to answer the following questions (Fellows’ responses have been edited slightly for length and clarity):

Q: What were the conversations and ideas that led to the formation of the VP of Inclusion and Wellness position, and the formation of the Panhellenic Inclusion and Equity Committee? Were there specific issues that led to their creation?

PF: “There weren’t specific DEI-related issues in the community that led to the creation of the position, we just wanted to be able to dedicate more time and space to DEI. Each position on the College Panhellenic Council is required to meet with its chapter counterparts … so VP Inclusion and Wellness is required to meet with the PIE Committee. This means that the VP Inclusion and Wellness does not select the PIE Committee or have any say in the officers; the chapters select each officer through their own selection processes.”

Q: How was the VP position and Committee formation received by the member sororities of the CPC?

PF: “The formation of the position and committee were well received. All positions struggle from time to time with participation … but it doesn’t seem to be because members of the community don’t care about DEI initiatives. Lack of participation tends to do with their own chapter programming and responsibilities.”

Q: After its formation, how were the initiatives laid out on the DEI web page decided upon?

PF: “Some of the initiatives had previously been implemented by the VP Community Wellness that I continued when I entered the [VP of Inclusion and Wellness] position. One of my biggest goals in this position was to make sure all members of our community felt safe, comfortable, and supported by their chapters and CPC.”

Q: What have been the most successful initiative processes so far?

PF: “I think the creation of the PIE Committee has been most successful. … I asked the committee what they wanted out of our roundtables, and everyone agreed on education they could bring back to their chapters. Many of the women on this committee have a background in DEI, but not everyone, and I wanted to make sure everyone had that foundation going into the year. Typically … I would give some sort of presentation regarding a DEI topic, and then each officer would discuss what they were currently doing in their position. I believe this conversation was especially helpful because it allowed everyone to … bring some ideas of programming back to their chapter.”

Q: What initiative processes have been most difficult to achieve?

PF: “The DEI survey was difficult, simply because many chapters had trouble reaching the required response percentage. I asked each chapter to have at least 85% of their members complete the survey … this was much more difficult than I anticipated. If I could redo the way I did the survey, I would offer some sort of incentive, or visit each chapter myself to ask members to complete the survey.”

Q: How have you communicated with demographic groups previously excluded? Have those outreach strategies been fruitful?

PF: “CPC reaches out to all women who we know are attending the university who are eligible for recruitment. I think if we were to specifically reach out to groups who have been excluded in the past, we would be dangerously close to tokenism. Instead, we operate under a “no-frills” or “values-based” recruitment, which means chapters are required to recruit based on Potential New Members’ values, rather than status, race, etc. We have also lowered the cost of signing up for recruitment to make it as accessible as possible….”

Q: How has the VP of Inclusion and Wellness office functioned thus far, and how would you like it to proceed in the future?

PF: “I think the VP Inclusion and Wellness office has functioned effectively so far, but there is [room] for improvement as the office grows. One thing I’ve encouraged the next officer to do is to bring in more guest speakers to PIE Committee meetings, or even CPC Council meetings. I’d also like the future VP Inclusion and Wellness to work with our VP Personnel and VP Recruitment to implement some sort of DEI training for Gamma Chis (recruitment counselors) and chapter recruitment chairs….”

Fellows’ responses illuminate the CPC’s fledgling efforts at becoming more inclusive. Her responses also highlight that these initiatives have struggled with participation from chapter members. Notably, Fellows’ response to the question about outreach to historically excluded and discriminated against women that the CPC does not reach out to them out of fear of “tokenism” echoes the argument from “Southern Sororities Face Black Issue” article from 1970.

To be clear, Fellows is not arguing that CPC sororities should be segregated, yet her fear of the CPC being seen as tokenizing is telling of a broader issue in these NPC and CPC DEI initiatives: they center around self-contained initiatives (such as roundtables, listening sessions, and self-education) which seem to be solely for the benefit of the mostly white women of these organizations, instead of centering on outreach to women affected by exclusionary practices. The CPC can continue with its race-neutral blanket outreach to “all women who are eligible for recruitment,” but—given the known reputation of historically white sororities as exclusionary organizations—most women who will bother to go through recruitment will continue to be white. This insular dynamic defeats the purpose of greater inclusion, thus making real the CPC’s fears of tokenism by turning their DEI initiatives into effectively symbolic efforts.

Of course, dealing with legacies of racism is a complex, difficult task that is both personal and political. But if the CPC is serious about becoming more inclusive, an actionable start would be to follow the example of Alpha Delta Pi’s and Delta Gamma’s national leadership. Gathering archival evidence of its own past exclusionary and discriminatory practices (and those of its member chapters), contextualizing that information, and confronting those legacies honestly and publicly is a meaningful step toward accountability. USM’s history department and the McCain Archives are both accessible resources the CPC could reach out to for assistance and guidance on such a project. Reckoning with decades of exclusionary and discriminatory practices will be a long and arduous process, and the CPC’s efforts are only a year old. Ideally, the CPC will engage with the broader campus community, including and especially women of color, and make bolder initiatives a priority as they expand their DEI efforts.

Bibliography

Dodge, Lisa, and Jess Gross Patterson. “Confronting Our Past: Understanding the Barriers to Inclusion.” Anchora (Winter 2019): 12-21. http://digital.watkinsprinting.com/publication/?m=3174&i=647238&p=1&pre=1&ver=html5.

Email correspondence between author and CPC President Paige Fellows, 29 November 2023.

National Panhellenic Conference. “NPC’s Commitment to Diversity, Equity, Access and Inclusion,” Priorities. https://npcwomen.org/priorities/npc-diversity-equity-inclusion/.

Southern Miss College Panhellenic Council. “Embracing All: CPC and DEI,” Community. https://www.southernmisscpc.com/dei-initiatives.

Wright, Elizabeth Lewis. “Owning Our Past: An Exploration of Membership Selection in Alpha Delta Pi’s History,” The Adelphean 124, no. 4 (Summer 2020): 6-19. https://editiondigital.net/publication/?m=17352&i=665883&p=6&ver=html5.