Project Objectives

The Roots of Community project examines the individual and collective histories of twelve segregated Carnegie libraries (or “Carnegie Negro libraries”, as they were called), a subgroup of tax-supported public libraries which opened between 1905 and 1924 as part of Andrew Carnegie’s (and later the Carnegie Corporation’s) well-known library building program. These libraries opened in Atlanta and Savannah (Georgia), Greensboro (North Carolina), Houston (Texas), Nashville and Knoxville (Tennessee), Louisville (Kentucky) (2 libraries), Meridian and Mound Bayou (Mississippi), New Orleans (Louisiana), and one north of Ohio River, in Evansville (Indiana). For decades these libraries served as learning spaces for African Americans in the pre-Civil Rights American South. By the 1960s, most had closed or had integrated with their communities’ formerly whites-only public library systems.

Despite the amount of available research about Carnegie libraries, comparatively little exists about these twelve segregated libraries. And while public historians, academic researchers and students of various fields may from knowing more about them—where they existed, how they were governed and managed, what conditions they were to follow per their Carnegie grants—these twelve libraries’ stories can also help today’s library professionals better understand how library users, especially those from marginalized groups, created and sustained a sense of community. This history can also help them enhance their library’s community knowledge programs, services and collections.

The Roots of Community project is the first comprehensive historical study of all twelve segregated Carnegie libraries and examines each library’s civic and economic origins, governance, spatial design, collections, use and place in the community. By drawing on documentary, archival, and other historical forms of evidence, it determines the extent to which African Americans in the pre-Civil Rights south used these libraries for community-making and identity-sharing. The project also seeks surviving users of these libraries and record their recollections and experiences as oral histories.

Project deliverables include monograph, a toolkit for library practitioners, and various materials for BlackPast.org, among other deliverables.

Andrew Carnegie and Public Libraries for African Americans

Carnegie libraries have been a regular topic of historical research for the past forty years. Put simply, these were libraries funded by the Scottish-born American steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie who, from 1898 to 1917, funded the construction of 1,689 public and academic libraries across the United States. General historical perspectives about Carnegie libraries are common, and provide a rich and detailed basis for understanding the social contexts and economic origins of the Carnegie library grant program in the United States, the program’s overall contributions to the development and spread of the modern free public library as a means for self-education and the spread of literacy, and, most especially, how Carnegie library buildings contributed in the early century to the standardization of power relations between people in public space.

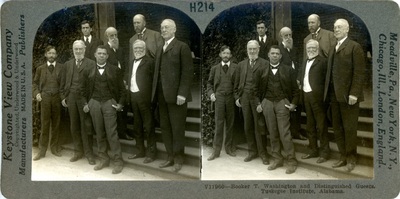

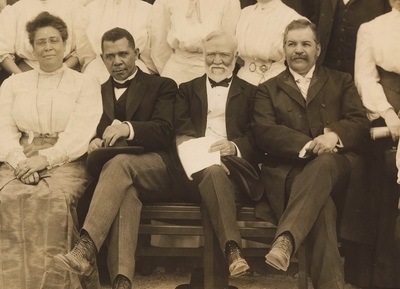

Carnegie’s first grants for African American libraries went to colleges. Between 1900 and 1915, Carnegie funded the construction of libraries at fifteen “colored colleges” in the United States. This part of his library grant program was a direct result of his association with Booker T. Washington, which began in 1899. The first of these libraries opened at Washington’s Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. The other fourteen colleges included: Alabama A&M, Atlanta University, Benedict College in South Carolina, Biddle University in North Carolina, Cheyney State University in Pennsylvania, Fisk University in Nashville, Florida A&M, Fort Valley Normal and Industrial Institute in Georgia, Howard University, Knoxville College, Livingstone College in North Carolina, Talladega College in Alabama, Wilberforce University in Ohio and Wiley College in Texas.

Yet while Carnegie’s library grant program flourished, government-funded library services to African Americans in the United States were still limited, especially in the pre-Civil Rights South where racial segregation laws (also known as “Jim Crow” laws, a term for the US state laws passed in the 1890s that legislated the separation of blacks from whites in the South in housing, public education, public facilities, and other areas) prevailed. In most southern communities, white attitudes summarily dismissed the need for library service of any kind for blacks.

While some whites-only public libraries at the time maintained “Negro reading rooms,” separate branches for African Americans were virtually non-existent. Despite this, only eleven communities in the entire United States opened libraries for African Americans through Carnegie’s program. Not only were these among the very first tax-supported public libraries for African Americans, they were also some of the earliest such libraries to occupy dedicated, purpose-built buildings in their communities. And as extensions of the broader Carnegie library grant program, these twelve libraries would have been subject to many of the same conditions of governance, taxation, and maintenance that Carnegie’s program typically imposed upon communities accepting his gifts. This alone makes these libraries landmarks of civic history. It also provides a basis to compare these communities’ segregated library buildings, services and collections with their whites-only counterparts.

Project Partners and Supporters

The project receives support and cooperation from several organizations. See below for more information about each.

BlackPast.org is a free, open access scholarly reference resource maintained by professional historians of African American history and culture. As its mission states, the resource “is dedicated to providing the inquisitive public with comprehensive, reliable, and accurate information concerning the history of African Americans in the United States and people of African ancestry in other regions of the world. It is the aim of the founders and sponsors to foster understanding through knowledge in order to generate constructive change in our society.”

The Aquila Digital Community, an open access digital repository and distributor maintained by the University of Southern Mississippi. It hosts many scholarly materials published by members of the university community, including digital journals, newsletters, reports and monographs. It also hosts websites that support various research projects by university faculty.

The Institute of Museum and Library Services supported this project with a three-year, LB21 Early Career Development research grant (IMLS # RE-31-16-0044-16). IMLS is the primary source of federal support for the nation’s 123,000 libraries and 35,000 museums. Its mission has been to inspire libraries and museums to advance innovation, lifelong learning and cultural and civic engagement. For the past 20 years, its grant making, policy development, and research has helped libraries and museums deliver valuable services that make it possible for communities and individuals to thrive. To learn more, visit www.imls.gov and follow the IMLS on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Project Director

Dr. Matthew R. Griffis completed his PhD at the University of Western Ontario’s Faculty of Information and Media Studies in London, Canada. He holds earlier degrees from Trent University and Queen’s University (Kingston) and completed additional graduate training in publishing and the book arts at the Centennial College School of Communication, Media and Design in Toronto. Dr. Griffis served the University of Southern Mississippi’s School of Library of Information Science as an Assistant Professor from 2013 to 2019 and as an Associate Professor from 2019 until 2022. Although no longer affiliated with the University of Southern Mississippi, Griffis remains the Roots of Community project’s director and is responsible for its ongoing objectives.

A longtime student of Carnegie libraries and their impacts on communities, Griffis began graduate work in 2006 on the development of modern public libraries and the nature of libraries as social space. His 2013 dissertation, Space, Power and the Public Library, explored the historically determined relationships of power, perception and actor control embedded within library designs from the late 19th to the early 21st centuries. As a doctoral candidate, Griffis assisted Dr. Catherine A. Johnson with her study of public libraries as builders of social cohesion in urban and rural communities, a project supported with a three-year grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Griffis has published work about public libraries as social spaces—most particularly as places of community, gathering and shared experience—in several academic journals, and has presented juried papers about public libraries as social spaces at numerous regional, national and international scholarly and professional conferences. In addition to the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) in Washington, DC, several other agencies have Griffis’s projects, among them the Canadian Library Association, the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) and the Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE).

Consultants

Two other researchers, Dr. Julie Hersberger of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and Dr. Eric Platt of the University of Memphis, served as consultants and reviewed selected deliverables during the project’s period of active funding (2016-19).

Dr. Hersberger is a former professional librarian and now a professor of libraries and information. She primarily studies social networks and relationship building and the information behavior of marginalized and oppressed groups. Published in 2007, her work about the segregated Carnegie library in Greensboro served as a basis for the Roots of Community project. An historian of education in the American South, Dr. Platt’s work focuses primarily on the role of institutions in educational infrastructure, the history of education for groups and minorities (including religious communities) and the place of informal learning in the daily lives of adults.