To read about each segregated Carnegie library, scroll down or click a link below:

Atlanta’s Auburn Branch Library (1921-59)

Evansville’s Cherry Street Library (1914-55)

Greensboro’s Carnegie Negro Library (1924-63)

Houston’s Colored Carnegie Library (1913-1961)

Knoxville’s Free Colored Library (1918-61)

Louisville’s Western Colored Branch Library (1905- )

Louisville’s Eastern Colored Branch Library (1914-75)

Meridian’s 13th Street Colored Branch Library (1913-74)

Mound Bayou’s Carnegie Library (1910-35?)

Nashville’s Negro Public Library (1916-49)

New Orleans’s Dryades Branch Library (1915-65)

Savannah’s East Henry Street Carnegie Library (1914- )

All profiles written by the Project Director, Dr. Matthew R. Griffis. Profiles have been previously published (some in slightly modified form) in BlackPast.org’s African American History online encyclopedia. Image credits appear where appropriate.

Reproduction of this content without written permission from the Project Director is strictly prohibited.

Materials not attributed to the author or the Roots of Community Collection remain property of their respective collections as noted below.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Atlanta’s Auburn Branch Library (1921-59)

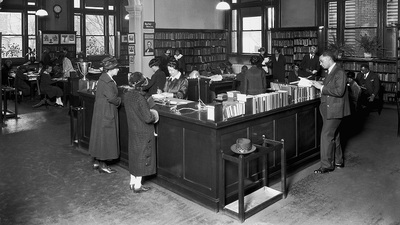

The Auburn Branch Library was a segregated branch of the Carnegie Library of Atlanta (now the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library). Opened in 1921, it was the first free public library in Atlanta for African Americans and one of twelve segregated public libraries in the south funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. Formerly located at 333 Auburn Avenue, the Auburn Branch closed in 1959. Among its notable former users was civic and political leader John Wesley Dobbs (1882-1961).

The Auburn Branch’s story began almost twenty years before the library opened. When the Carnegie Library of Atlanta (CLA) was established in 1902 with a $125,000 grant from Andrew Carnegie, it did not allow black users. Representatives from Atlanta’s African American community, including Atlanta University professor W.E.B. DuBois (1868-1963), demanded that the CLA provide access to blacks. DuBois questioned the legality of using tax money from blacks (who represented about a third of Atlanta’s population at the time) to support a whites-only public library. The CLA’s trustees not only refused to provide access, they also denied DuBois’s request for black representation on their board. They proposed opening a separate library for blacks instead. But after receiving an offer of $10,000 from Carnegie in 1904 for a “colored” branch, neither the city nor the CLA advanced the project.

Atlanta’s black citizens nevertheless continued lobbying for a black public library. When Tommie Dora Barker (1888-1978) became Librarian of the CLA in 1916, she took up the cause and eventually secured $25,000 from the Carnegie Corporation. Despite further setbacks, Atlanta’s new “colored” library finally opened on July 25, 1921. A one-story, brick structure, the Auburn Branch Library was built on the southwest corner of Auburn and Hilliard streets, in the heart of what was then the largest black districts in the South. The Auburn Branch received an annual appropriation from the city and, for its first few years at least, was represented by a “Negro Advisory Committee” that worked directly with the CLA’s trustees.

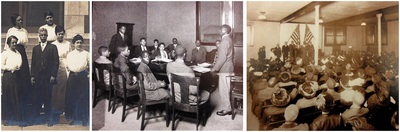

Under the supervision of its first librarian, Mrs. Alice Dugged Carey (1859-1941), the Branch quickly became one of the Auburn community’s social and intellectual centers. Over its four decades of service, the Auburn Branch offered Atlanta’s black citizens not only thousands of books and magazines to read but also story hours and reading clubs for youth, book discussion groups for adults, and meeting space for countless community organizations. It also formed close partnerships with other black educational institutions and community organizations and established a shut-in borrowing service for hospital patients. When Annie L. McPheeters (1908-94) became the Branch’s librarian in 1934, she established its Negro History Collection, a non-circulating research collection dedicated to African American studies and the history of Atlanta’s black community.

The Auburn Branch’s popularity lasted until the late 1940s, when many of Auburn’s residents began migrating west. When a second segregated library, the West Hunter Branch, opened in the west end of town in 1949, use of the Auburn Branch steadily declined. It finally closed in 1959 and the building was razed in 1960. Today, the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, located just blocks from where the Auburn Branch once stood, maintains the former library’s Negro History Collection, now part of the Samuel Woodrow Williams Collection on Black America.

Sources: Barbara Mamie Adkins, A History of Public Library Service to Negroes in Atlanta, Georgia (Atlanta University: Master’s Thesis, 1951); Cheryl Knott, Not Free, Not for All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015); Annie L. McPheeters, Library Service in Black and White: Some Personal Recollections, 1921-1980 (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1988).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System

>Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History

>>Auburn Branch Library Records

>>Annie L. McPheeters Papers

University of Georgia Libraries

>Digital Library of Georgia

Georgia State University Library

>Digital Collections

Atlanta History Center

>Kenan Research Center

>>Tommie Dora Barker Papers

University of Massachusetts-Amherst

>W.E.B. DuBois Papers

Related Oral Histories (online):

McPheeters, Annie L. (1992-06-08, GSU Special Collections)

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Evansville’s Cherry Street Library (1914-55)

The Cherry Street Library was a segregated branch of the Evansville Public Library (now Evansville Vanderburgh Public Library) located at 515 Cherry Street in Evansville, Indiana. It was the first free public library built north of the Ohio River exclusively for African Americans and one of twelve segregated public libraries funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie (the remaining eleven located in the South). The Cherry Street Library opened in November 1914 and closed in July 1955.

The Cherry Street Library’s story began in 1911, when the Evansville Public Library accepted a $50,000 grant from Andrew Carnegie for two libraries, the West and East branches, both completed in 1912. These libraries did not provide service to African Americans. In late 1912, Chief librarian Ethel Farquhar McCollough convinced the Evansville Public Library’s board of trustees to approach Carnegie about a separate branch library for the city’s African Americans. Carnegie donated $10,000 towards the branch in May 1913.

Local firm Clifford Shopbell & Co. designed the building, whose exterior was of light-yellow brick and Bedford stone. Its main floor included reading rooms for adults and children and in its basement an auditorium contained seating for eighty. But unlike other segregated public libraries of the period, the Cherry Street Library was not managed by a separate, African American board; it was the domain of the local (white) library board. Evansville’s population at the time was almost 60,000, only about 6,200 of which were black. But the library’s location on the corner of Cherry and Church streets placed it at the center of Baptistown, Evansville’s “negro district” at the time. It was near many segregated public schools and large churches, among them the Liberty Baptist Church. The finished library opened in November 1914.

For over four decades, the Cherry Street Library provided an intellectual center for Evansville’s African Americans. It loaned nearly 2,000 books in its first month and by 1917 circulation had increased to over 15,000 loans a year. The library was equally successful as a community center, offering literary clubs for adults and children, hosting story hours and gardening contests, and organizing holiday parties and clothing drives for the disadvantaged. Its meeting rooms served countless community organizations and groups, among them the local chapter of the NAACP, the Red Cross, local unions and music clubs; and its auditorium was the stage for many public lectures and musical performances. Cherry Street’s first Branch Librarian was Fannie C. Porter; Lillian Childress Hall, the Indiana Library Commission Summer School’s first African American graduate, took over in 1915. Later librarians included Martha Roney, Minnie Slade, Thelma Rochelle and Bernice Hendricks. One of the branch’s Assistant Librarians, Anna Cowen Bucker, was the wife of Dr. George W. Buckner, a physician, teacher and former U.S. Diplomat to Liberia.

Despite its popularity, use of the Cherry Street Library began to decline in the 1940s. By 1952, the year Evansville desegregated its library facilities, much of the city’s African American population had migrated away from Baptist Town and closer to the Lincoln Gardens neighborhood. The Cherry Street library closed in July 1955 and was later sold to a local Boy Scout troop. The building remained an architectural landmark until 1971, when it was razed to make room for an expanding hospital facility.

Sources: Michele T. Fenton, “Way Down Yonder at the Cherry Street Branch: A Short History of Evansville’s Negro Library,” Indiana Libraries 30:2 (2011); Michele T. Fenton, “Stepping Out on Faith: Lillian Childress Hall, Pioneer Black Librarian,” Indiana Libraries 33:1 (2014); Herbert Goldhor, The First Fifty Years: The Evansville Public Library and the Vanderburgh County Public Library (Evansville, IN: No publisher identified, 1962).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Evansville African American Museum

Evansville Vanderburgh Public Library

>Digital Archive

>Indiana Room (Central Library)

Indiana State University Special Collections

University of Southern Indiana Archives and Special Collections

>African American Community Gallery

>Evansville Argus Newspaper Collection

>Evansville History Gallery

>Oral History Collections

Willard Library of Evansville

>Evansville Historic Photo Collection

__________________________________________________________________________________________

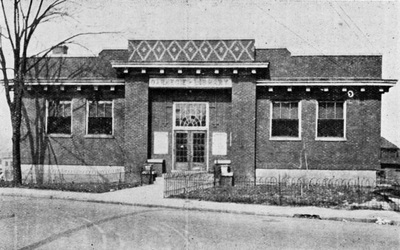

Greensboro’s Carnegie Negro Library (1924-63)

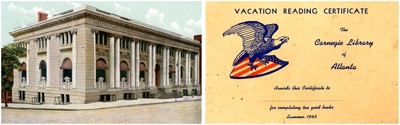

The Carnegie Negro Library of Greensboro, North Carolina was a free public library for African Americans opened in 1924. It stood at 900 East Washington Street on the Bennett College campus. It was the last of twelve public libraries for African Americans opened in the South between 1908 and 1924 and funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. Until the 1950s, the Negro Library was Greensboro’s only free public library to serve African Americans. It operated as an independent, free public library for blacks until 1963.

The Carnegie Negro Library’s story began in 1905, when Andrew Carnegie offered Greensboro $10,000 to build a segregated library. The philanthropist had already donated $30,000 towards Greensboro’s main library building, which was completed in 1906 on the corner of Gaston Street and Library Place. Greensboro’s population at the time was 10,035 people, just over 40% (4,086) of which were African American (per the 1900 census). But prolonged debates over proposed sites prevented any action until 1916, when Bennett College offered a site on its campus, in the residential heart of Greensboro’s “negro district.” Some opposed the plan, claiming that the grounds of a private institution were not ideal for a publicly funded library. Controversy delayed the project until 1923, but the library was eventually completed and opened in October 1924.

Although the Negro Library received an annual tax appropriation from the city, it was governed by an independent Board of Negro Trustees, appointed by City Council in 1924. Measuring just over 2,000 square feet, the building was small, as was its original collection of just 150 volumes. But under the leadership of Martha Sebastian, who served as Head Librarian until her death in 1948, the Carnegie Negro Library blossomed into one of the African American community’s most vital intellectual centers. Sebastian, whose husband was Dr. Simon Powell Sebastian (Director of the former L. Richardson Memorial Hospital), grew the library’s collections quickly. She even began an African American literature collection in 1925. By 1930, the library’s circulation was the largest of any segregated public library in the state. The Negro Library also served as an important gathering place for many of Greensboro’s African American community organizations, for example the Greensboro Art Center, which used the library’s basement as its headquarters in the 1930s. The library offered book discussion groups, daily story hours and seasonal reading clubs for children. When Martha Sebastian passed away in 1948, Mrs. Willie Grimes took over as Head Librarian and remained until her retirement in 1963.

In some ways, the Negro Library’s success helped contribute to its decline. Demand for books only increased the size of its collections, and by 1955 nearly 28,000 volumes filled the small building. A bookmobile program launched in 1945 helped alleviate space issues and extended the Negro Library’s services into rural parts of the county. But by 1960, the library had all but run out of space. Following desegregation of Greensboro’s libraries in 1957, the Negro Library merged with the city library system in 1963, retiring its autonomous board. It served as the Southeast Branch of the Greensboro Public Library until a new library (today the Vance Chavis Branch) opened in 1966, closing the older branch permanently. The former Negro Library building remains standing and currently houses Bennett College’s Truth and Reconciliation Archives.

Sources: Ethel Stevens Arnett, Greensboro, North Carolina: The County Seat of Guildford (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1955); Julia A. Hersberger, Lou Sua and Adam L. Murray, “The Fruit and Root of the Community: The Greensboro Carnegie Negro Library, 1904-1964,” in The Library as Place: History, Community and Culture, edited by John E. Buschman and Gloria J. Leckie (Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2007); Helen Snow, The Greensboro Public Library: The First 100 Years (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning, 2003).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Bennett College Thomas F. Holgate Library (Archives and Special Collections)

>Bennett College Historical Photos

>Constance Hill Martina Papers

Greensboro History Museum

>Collections and Archives

Greensboro Public Library (Central Library)

>North Carolina Collection

>Vance Chavis Library (branch)

North Carolina A&T State University F.D. Bluford Library and Archives

>Dr. Simon Powell and Martha J.O. Sebastian Collection

State Library of North Carolina

>Digital Collections

UNC Greensboro Special Collections and University Archives

>Civil Rights Greensboro Oral History Interviews

>Digital Collections

>UNCG Institutional Memory Collection

Related Oral Histories (online):

Chavis, Vance H. (1973-05-28, 1979-11-21 and 1988-12-06, UNCG Collections)

Dowdy, Lewis (1975-01-21, UNCG Collections)

Sims, Sheila Cunningham (2012-04-12, UNCG Collections)

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Houston’s Colored Carnegie Library (1913-1961)

The Colored Carnegie Library was a segregated branch of the Houston Lyceum and Carnegie Library (later the Houston Public Library). It opened in 1913 in Houston’s Fourth Ward. It was one of the first public libraries for African Americans west of the Mississippi and one of twelve segregated public libraries originally funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie between 1908 and 1924.

The Colored Carnegie Library’s story began in 1907, when Houston’s public library denied service to a group of African American teachers. The city had received $50,000 from Andrew Carnegie in 1899 for their public library, which opened in 1904 on the corner of McKinney and Travis (now Main) streets. But while nearly 40% of Houston’s population at time (44,600 people) was black, the city offered no comparable library services to African Americans. In response, a committee led by educator Ernest Smith opened a small, one-room library in the Fourth Ward’s Colored High School in 1909. They also approached the city’s Chief Librarian, Julia Ideson, and Mayor H. Baldwin Rice to request a separate “colored library” grant from Carnegie. Following additional support from Booker T. Washington (whose assistant, Emmett J. Scott, was Houstonian), their application was approved in 1909. Carnegie donated $15,000 and the Colored Carnegie Library opened in 1913.

The new library quickly became a symbol of civic autonomy for Houston’s African Americans. Its architect was William Sidney Pittman, son-in-law of Booker T. Washington. And more, though the Colored Carnegie Library received tax support from the city, it did not operate as a branch of the city’s (white) public library. It was governed by the Colored Carnegie Library Association, an independent board of African American leaders. The library also stood at the corner of Frederick and Robin streets, in the heart of the city’s Fourth Ward, then considered Houston’s “colored district.” It was near several public schools and directly across from one of the community’s largest churches, the Antioch Baptist Church. The library’s opening in 1913 made headlines in black newspapers across the country, including The New York Age.

The Colored Carnegie Library remained vital to Houston’s African American community for nearly five decades. Though it reopened as a branch of the city’s main library in 1921 (thereby dissolving its independent board), the Colored Carnegie Branch organized many reading programs and book clubs, accumulated important collections of African American literature and history, hosted many guest speakers, helped local teachers and schoolchildren, and offered night classes for adults. Local organizations and clubs gathered regularly in the library’s meeting rooms, among them the Negro Art Guild of Houston and the local chapter of the NAACP. Branch librarians included Bessie Osborne, James Hulbert, Florence Bandy and Willie Bell Anderson.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Houston Public Library expanded its services to African Americans. They opened a branch at Emancipation Park, installed deposit stations at many black public schools and launched a separate bookmobile serve in the 1950s. Though Houston desegregated its libraries in 1953, the Colored Branch continued to serve a predominantly African American clientele for most of its remaining years. Use of the library declined throughout the 1950s however, until the Colored Branch finally closed in 1961. The building was demolished the following year during the city’s Clay Street extension project.

Sources: David M. Battles, The History of Public Library Access for African Americans in the South (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 2009); Cheryl Knott, Not Free, Not For All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow (Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015); Cheryl Knott Malone, “Autonomy and Accommodation: Houston’s Colored Carnegie Library, 1907-1922,” Libraries & Culture 34:2 (Spring 1999).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Houston Public Library Special Collections

>African American Library at the Gregory School

>Houston Metropolitan Research Center

>Houston Oral History Project

>Houston Area Digital Archives

Morgan State University Beulah M. Davis Special Collections

>Emmett Jay Scott Collection

University of Houston Libraries Special Collections

Related Oral Histories (online):

Bryant, Thelma Scott (1981-10-21a, 1981-10-21b and 2007-08-03, HPL Collections)

Hartwell, Willie (2018-06-02, ROC Project Collections)

Ross, Myrtle (2018-07-16, ROC Project Collections)

__________________________________________________________________________________________

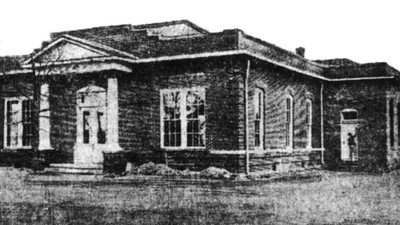

Knoxville’s Free Colored Library (1918-1961)

The Free Colored Library of Knoxville, Tennessee was a segregated public library opened in 1918 and closed in 1961. It was the first municipally-supported library for African Americans in Knoxville, Tennessee and one of twelve segregated public libraries opened in the South between 1908 and 1924 and funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie.

Knoxville founded its municipal library, the Lawson McGhee Library, in 1883. It reopened in 1914 as a free public library but still served only whites. After the McGhee Library denied service to several African American teachers in 1915, one of these teachers, school principal Charles Warner Cansler, approached Mayor Samuel G. Heiskell for help in obtaining a grant from Andrew Carnegie for a library for the city’s blacks. Knoxville’s population at the time was over 36,000 people, about 21% of which were African American. In 1916, the philanthropist donated $10,000 towards the library, which opened on the corner of Nelson Avenue and East Vine Street in May 1918. Local architect Albert B. Bauman Jr. designed the facility, whose main floor contained a reference room and separate reading rooms for adults and children. Its basement contained meeting rooms and a large auditorium. Like most segregated public libraries at the time, Knoxville’s Free Colored Library did not open under its own board of African American trustees; it operated as a branch of the city’s Lawson McGhee Library, which was governed by an all-white board.

The Free Colored Library served Knoxville’s African American community for over forty years as an intellectual center, recreation center and community gathering place. Upon the library’s opening in 1918, Charles Warner Cansler remarked: “The building will have served its purpose only in part if it becomes only the center of the activities of the reading colored people of this community. There is not today in the city of Knoxville … a single decent place, with the exception of stores or offices, where a colored man or woman can go for rest and relaxation.” It circulated thousands of books and magazines for reading, study and improvement, and provided space for clubs and community organizations to gather. It established and maintained beneficial relationships with many segregated public schools and offered students reading clubs to join in the summer. Mary M. Miller was its first Branch Librarian; her replacement in 1924 was J. Herman Daves, who later taught sociology and economics at Knoxville College and even later served as the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Supervisor of Negro Education. Later Branch Librarians included Sallye Juanita Long-Carr and Goldie Carter.

Despite establishing an adjunct Negro Advisory Board in the 1950s, the Free Colored Library (later known as the Colored Library Branch) began to decline in use. It closed in 1961 and was later demolished. A second segregated branch, the Murphy Branch Library, opened in 1930 and continued to serve Knoxville’s African Americans after the Free Colored Library closed.

Sources: C.W. Cansler, “A Library Milestone,” Public Libraries 24 (January 1919); J.H. Daves, A Social Study of the Colored Population of Knoxville, Tennessee (Knoxville, TN: Free Colored Library, 1926); Cheryl Knott, Not Free, Not For All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow (Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015); Ernest I. Miller, “Library Service for Negroes in Tennessee,” Journal of Negro Education 10:4 (1941).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Knox County Public Library

>Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection

>>Digital Collections

>Lawson McGhee Library

University of Tennessee Knoxville Special Collections

Related Oral Histories (online):

Daves, J. Herman (1972-02-13, U of M Collections via Internet Archive)

__________________________________________________________________________________________

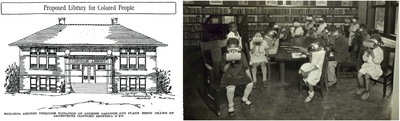

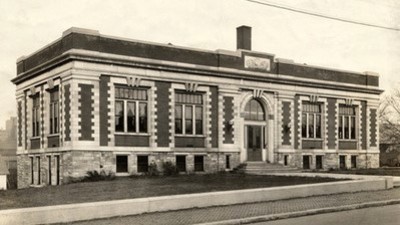

Louisville’s Western Colored Branch Library (1905- )

The Western Colored Branch Library was a segregated public library in Louisville, Kentucky, first opened in 1905. It was the first free public library for African Americans in the United States and its building of 1908 was one of twelve segregated public library buildings funded by Andrew Carnegie’s library development program of the early century. It was added to the National Register of Historical Places in 1975 and operates today as the Western Library, an integrated branch of the Louisville Free Public Library system.

The force behind the Western Colored Branch’s foundation was Albert E. Meyzeek (1862-1963), an African American educator who, in 1902, protested the Louisville Free Public Library’s exclusion of African Americans from its libraries. The library board, which had obtained $450,000 from Andrew Carnegie for a new main library building and eight neighborhood branches, agreed in 1905 to open a “colored branch” at 1125 West Chestnut Street in west Louisville’s predominantly black neighborhood. The library occupied rented rooms until October 28, 1908, when it reopened in a handsome, $35,000 building located at 604 South 10th Street. Unlike some later segregated public libraries in the south, however, the Western Colored Branch was not governed by a separate board of black civic leaders. It operated under the white board of the Louisville Free Public Library. The branch was nevertheless well received by its users. It offered collections for adults and children as well as books by both white and black writers. It also hosted many clubs, held popular story-telling contests for children and teens, and provided public meeting space in its basement. The Western Colored Branch was so well received that in 1914 the Louisville Free Public Library opened a second segregated library, the Eastern Colored Branch, in east Louisville’s Smoketown neighborhood.

Over their decades of service, both “colored” branches became important educational support and community social centers for the city’s African Americans. They also served as models for other segregated libraries in the south. Behind much of the Western Branch’s early success was its inaugural head librarian, the Reverend Thomas Fountain Blue (1866-1935), and its original children’s librarian, Rachel D. Harris (1869-1969), now both considered African American pioneers of librarianship. From 1912 to 1931, Blue (and later, with Harris) operated a librarian training program at the Western Branch which until 1925 remained the only librarian training program in the country open to African Americans. Blue and Harris also helped improve library collections in Louisville’s segregated public schools.

The Western Colored Branch operates today as the Western Library, an integrated branch of the Louisville Free Public Library system. Though no longer segregated, it remains in its Carnegie building of 1908 and serves a predominantly African American neighborhood. The library also maintains extensive special collections dedicated to African American studies and the history of Louisville’s black community. Among the Western Colored Branch’s former users is Houston A. Baker, the distinguished scholar of African American studies.

Sources: Cheryl Knott Malone, “Louisville Free Public Library’s Racially Segregated Branches, 1905-35,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 93:2 (Spring 1995); Cheryl Knott, Not Free, Not for All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015); Joshua D. Farrington, “Western Colored Branch Library (Louisville),” The Kentucky African American Encyclopedia (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2015).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Louisville Free Public Library

>A Separate Flame: Louisville’s Western Branch

>Western Branch Library African American Archives

>Reverend Thomas F. Blue Papers

University of Kentucky Libraries

>Notable Kentucky African Americans Database

University of Louisville Libraries

>African American Oral History Collection

>Caufield and Shook Collection

>Digital Collections

>Louisville Leader Collection

Related Oral Histories (online):

Baker, Houston A. (2017-02-27, ROC Project Collections)

Edwards-Hunter, Karen (2017-04-25, ROC Project Collections)

Hutchins, Walter T. (1999-00-00, KHS Collections)

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Louisville’s Eastern Colored Branch Library (1914-75)

The Eastern Colored Branch was a segregated public library located at 600 Lampton Street in Louisville, Kentucky. Opened in 1914, it was the second of the city’s “colored” libraries and served Louisville’s east end. The Western Colored Branch, which opened in 1905, was the first free public library in the United States for African Americans. Both branches were among the twelve segregated public libraries funded by Andrew Carnegie’s library program of the early century. The Eastern Branch closed in 1975.

The force behind the Western and Eastern Colored branches was Albert E. Meyzeek (1862-1963), an African American educator who in 1902 protested the Louisville Free Public Library’s exclusion of African Americans from its libraries. The library board, which had obtained $450,000 from Andrew Carnegie for a main library and eight branches, agreed in 1905 to open the Western Colored Branch in Louisville’s predominantly middle-class Russell neighborhood. Reopened in 1908 in a Carnegie building on South 10th Street, the Western Colored Branch offered collections for adults and children as well as books by white and black writers. It also hosted many clubs, held popular story-telling contests for youth, and provided public meeting space in its basement. Impressed with the Western Colored Branch’s success, Meyzeek and Reverend C.C. Bates began lobbying for a branch in the east end. The Eastern Colored Branch opened on January 28, 1914, making Louisville the only city in the United States at the time with two segregated libraries. The Eastern Colored Branch was also the eighth and last library Louisville built with its Carnegie funds.

Like its west end counterpart, the Eastern Colored Branch operated under the Louisville Free Public Library’s board and was supervised by Thomas Fountain Blue (1866-1935). However, the Eastern Colored Branch served a considerably poorer neighborhood. It also housed considerably fewer books, at least in its early years. And despite its nearly identical size, the $19,000 Eastern Colored Branch building had cost substantially less than the $35,000 Western Branch. Still, the Eastern Branch was an instant success, serving over 14,000 of Louisville’s east end residents in its first seven months of service.

Over their decades of service, both “colored” branches became important educational support and community social centers for Louisville’s African Americans. They also served as models for other segregated libraries in the south. Behind much of their success was their head librarian, Thomas Fountain Blue, and the Western Colored Branch’s original children’s librarian, Rachel D. Harris (1869-1969), now both considered African American pioneers of librarianship. When Blue became head of the Louisville Free Public Library’s Colored Department in 1920, Harris relocated to the Eastern Colored Branch to serve as its Senior Assistant.

But while the Western Colored Branch still operates as an integrated branch of the Louisville Free Public Library system, the Eastern Colored Branch closed on December 31, 1975. Its former building remains on the corner of Hancock and Lampton streets.

Sources: Beatrice S. Brown, Louisville’s Historic Black Neighborhoods (Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia, 2012); Joshua D. Farrington, “Eastern Colored Branch Library (Louisville)”, The Kentucky African American Encyclopedia (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2015); Cheryl Knott Malone, “Louisville Free Public Library’s Racially Segregated Branches, 1905-35,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 93:2 (Spring 1995).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

See entry for Louisville’s Western Colored Branch (above).

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Meridian’s 13th Street Colored Branch Library (1913-1974)

The 13th Street Colored Branch was a segregated public library established by the city of Meridian, Mississippi in 1912 and opened in March 1913. It was one of the first free public libraries for African Americans in the state of Mississippi and one of twelve segregated libraries funded by Andrew Carnegie during his library philanthropy program of the early twentieth century.

Although Meridian asked Carnegie for library funds as early as 1904, it was not until 1911 that the library program’s manager, James Bertram, offered the city $30,000 for a main, whites-only library and $8,000 for a “colored” branch. At the time, African Americans accounted for almost one full third of the city’s population. The two-story, main library was built on the corner of 7th Street and 25th Avenue in the city’s downtown, while the segregated library was built on the corner of 13th Street and 28th Avenue in Meridian’s northwest, then known as the “colored” part of town. The Haven Institute, a small black college located on 13th Street, was instrumental in establishing the library; the African Methodist Episcopal Churches, which operated both the Haven Institute as well as one of Meridian’s oldest black churches, St. Paul’s Methodist, donated a site for the library.

Although the “Colored Library” received an annual tax appropriation from the city, it was governed by the Colored Library Advisory Board, a separate board whose inaugural chairman was Dr. J. Beverly Shaw of the Haven Institute. The institution’s first librarian was Mary Rayford Collins; later librarians included Helen Strayhorn, Katherine Mathis and Gradie Clayton, among others.

For over sixty years the 13th Street library served Meridian’s African Americans as both an educational support center and a community meeting space. When Meridian desegregated its public libraries in 1964, the separate advisory board dissolved and the 13th Street library became a branch of the Meridian-Lauderdale Public Library. It nevertheless continued to serve the predominantly African American northwest part of town.

The city closed the 13th Street Library in September 1974, claiming that it was no longer usable as a public building. The former library was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 and, in 2006, the Lauderdale County Human Relations Commission announced plans to convert it into a center for arts education. It was demolished in 2008, however, after it was deemed unsuitable for preservation. Only a piece of its front walkway remains. In February 2019, the city erected an historical plaque at the library’s former site.

Sources: Jeanne Broach, The Meridian Public Libraries: An Informal History, 1913-74 (Meridian, MS: Meridian Public Library, 1974); Matthew Griffis, “A Separate Space: Remembering Meridian’s Segregated Carnegie Library, 1913-74,” Mississippi Libraries 80:3 (Fall 2017); Cheryl Owens, “Study Stirs Memories of Segregated Library in Meridian,” The Meridian Star, March 4, 2017.

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Amistad Research Center (New Orleans)

>Collins Family Papers (1889-1988)

Lauderdale County Department of Archives and History

Meridian-Lauderdale County Public Library

Related Oral Histories (online):

Turner, Maxine (2017-01-12, ROC Project Collections)

Wilson, Jerome (2016-11-19, ROC Project Collections)

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Mound Bayou’s Carnegie Library (1910-35?)

Constructed in 1910 with a grant from Andrew Carnegie’s library development program, the Carnegie Library of Mound Bayou, Mississippi was the first free public library intended for African Americans in the state of Mississippi and one of the first African American public libraries in the country. It served as both a reading room and a community assembly hall until fire destroyed it in the 1930s. Its architect, William Sidney Pittman, who would later design the segregated Carnegie branch library in Houston, Texas, is the only African American known to have designed a Carnegie public library building.

The library was one of Mound Bayou’s key civic developments between 1905 and 1915, a period of substantial growth that began with the opening of the Bank of Mound Bayou in 1904 and peaked with the completion of the town’s ill-fated Oil Mill and Manufacturing Company in 1912. Charles Banks, a local businessman, had helped establish both institutions. A protégé of Booker T. Washington’s, Banks was also founder of the Mississippi Negro Business League and one of Mound Bayou’s most influential citizens. He agreed with mayor B. Howard Creswell that a free public library would improve the region’s educational infrastructure. When Banks wrote his first letter to Andrew Carnegie in January 1909, the philanthropist responded just three weeks later, offering Mound Bayou $4,000 for a library. It remained the only public library grant Carnegie offered to a black town in the United States.

Mound Bayou built its one-story, red-brick library on the southwest corner of Green and Fisher streets, diagonal from the Normal and Industrial Institute. Its builder was Thomas W. Cook and its architect was William Sidney Pittman, a Tuskegee graduate and son-in-law of Booker T. Washington. However, soon after opening the library in December 1910, Mound Bayou struggled to maintain it as a public library. Though its payroll included a custodian, the library contained few furnishings and no books, only newspapers and magazines. Within a year, town council had already neglected its financial obligation to the library. Tensions increased when Carnegie learned that the local Masonic Benefits Association was renting part of the building for its offices. The situation did not improve when a crash in cotton prices crippled the town’s industrial anchor, the Oil Mill and Manufacturing Company. State regulators closed the Bank of Mound Bayou in 1914, sending the town into further decline.

Mound Bayou’s citizens nevertheless used their Carnegie Library for a variety of community purposes, including public meetings, business league meetings, farmer’s conferences, and fundraising events. The nearby Normal and Industrial Institute and Bolivar County Training School also used the library for classes. Though a donation of 200 books boosted the library’s collections in 1912, it is unclear whether the library ever contained enough books to support the town of 1,500. In 1925, the City Federation of Women’s Clubs offered to reopen and maintain the building as a fully operational public library. But whether the town accepted their proposal is unclear. The Carnegie library is believed to have been lost in 1935 when a fire destroyed much of Mound Bayou’s business district. The library was not rebuilt.

Sources: Hood, Aurelius P. and Marshall Frady, The Negro at Mound Bayou: Being an Authentic Story of the Founding, Growth and Development of the “Most Celebrated Town in the South,” Covering a Period of Twenty-Two Years (Nashville: A.M.E. Sunday School Union, 1910); Jackson Jr., David H., A Chief Lieutenant of the Tuskegee Machine: Charles Banks of Mississippi (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002); Rosen, Joel Nathan, “Mound Bayou,” The Mississippi Encyclopedia (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2017).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Delta State University Library and Archives

>Oral History Collections

Mississippi Department of Archives and History

University of Virginia Special Collections Library

>Jackson Davis Collection of African American Photographs

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Nashville’s Negro Public Library (1916-1949)

The Negro Public Library (later the Negro Branch of the Nashville Public Library) operated for over thirty years as a segregated library facility in Nashville, Tennessee. It was the city’s first public library for African Americans and one of only a dozen segregated public libraries in the South funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie and built between 1908 and 1924. Formerly situated on the southeast corner of Hines and Twelfth Avenue North, the Negro Public Library closed in 1949.

Carnegie’s library building program was well-known in Nashville by 1912. In 1901, the philanthropist had granted $100,000 for a main public library (completed in 1904 on Polk Avenue) and $20,000 in 1905 for Fisk University’s library, one of only fifteen Carnegie Negro College Libraries ever opened in the United States. With encouragement from city librarian Mary Hannah Johnson and the local Negro Board of Trade, Nashville’s city council successfully obtained a second grant from Carnegie in 1912: $50,000 for two branch libraries, one for whites and the other for blacks ($25,000 each). The city’s population at the time was just over 36,500 people, about 33% of which were African American. The whites-only North Nashville Branch opened in 1915 and the Negro Public Library in 1916. Though Fisk’s library served the occasional non-student, the new branch on Hines and Twelfth Avenue North would be Nashville’s first public library for African Americans. It offered separate reading rooms for adults and children on its main level and an auditorium and meeting rooms in its basement.

For thirty-three years, the Negro Public Library served as a center for intellectual development and community life for Nashville’s African Americans. Over 26,000 people registered as borrowers in the library’s first year. Its location in Nashville’s downtown was nevertheless unusual, since segregated libraries in the Jim Crow south usually opened in their city’s “negro district”—a safe distance from whites. But the city had built the Negro Branch near Fisk University’s original campus, situating it within reach of many of Nashville’s black residents. Community organizations like Boy and Girl Scouts and the Colored Women’s Chapter of the American Red Cross met regularly at the library. Its opening day collection was only about 2,500 volumes, most of which were by white authors. But the Negro Public Library would soon develop a significant collection of African American literature, including writings by Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois, subscribe to many important black periodicals of the day, from local black newspapers like the Nashville Globe to scholarly serials like the Journal of Negro History. The branch’s first librarian was Fisk graduate Marian McKenzie Hadley; later branch librarians included Olivia Carr Greenway, Hattie Watkins and Ophelia Lockhart. Under their guidance, the Negro Public Library engaged in many outreach activities, providing services to disadvantaged groups and establishing satellite branches in segregated public schools.

The Negro Public Library closed in 1949, several years before Nashville desegregated its library facilities. The former branch building was later demolished to make room for the Nashville Electric Service, whose building still occupies the site today. The city later placed the Negro Branch’s cornerstone in the courtyard of its Ben West Library, which opened in 1962. Newer branches, for instance the Hadley Park Branch Library, would continue serving a predominantly African American clientele long after the Negro Public Library’s closure.

Sources: David M. Battles, The History of Public Library Access for African Americans in the South (Lanham, MD: Scraecrow, 2009); Carol Farrar Kaplan, “Nashville’s Negro Carnegie Library 1916-1949,” unpublished paper in the Special Collections Division, Nashville Public Library (1997); Linda T. Wynn, “The Negro Branch of the Carnegie Library: Nashville’s First African-American Athenaeum 1916-1949,” Leaders of Afro-American Nashville (Nashville, TN: Metropolitan Historical Commission, 1997).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Nashville Metropolitan Government Archives

>Nashville Public Library Collection

Nashville Public Library

>Special Collections

>>Civil Rights Collection

>>Civil Rights Room

>>Digital Collections

__________________________________________________________________________________________

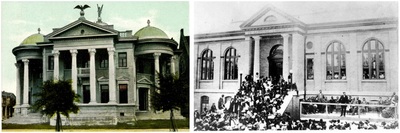

New Orleans’s Dryades Branch Library (1915-1965)

The Dryades Branch of the New Orleans Public Library was the first municipally-supported library for African-Americans in New Orleans and one of a dozen public libraries in the South established for African-Americans between 1908 and 1924 and funded by Andrew Carnegie. Opened in 1915, the branch operated for fifty years until hurricane damage permanently closed it in 1965.

The story of the Dryades Branch begins in January 1897, when the newly established New Orleans Public Library opened in St. Patrick’s Hall at Lafayette Square. Though the library’s reading room admitted black attorneys to access law books, it generally did not allow African Americans to register as borrowers. In 1906, New Orleans’s city council secured $250,000 from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie for the construction of a new central library and four branches. Located on St. Charles Street at Lee Circle, the central library opened in 1908. The Royal, Algiers, Napoleon and Canal branch libraries opened between 1907 and 1911. Still, none of the city’s public libraries admitted African Americans. The first step towards a “colored branch” did not occur until December 1911, when the Library Board’s president, James Hardy Dillard, requested additional funds from Carnegie. A professor and former president of Tulane University, the Virginia-born Dillard (for whom Dillard University would be named in 1930) was an educational reformer who sought to improve opportunities for African Americans. With help from local clergyman Robert E. Jones, and further encouragement from Booker T. Washington, Dillard secured $25,000 for a segregated library.

After considering at least two sites for the branch, in 1913 the Library Board purchased land at the intersection of Philip and Dryades streets in a neighborhood “largely of colored people.” It was adjacent the Colored YMCA and a short walk from several churches. Now Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard, this stretch of Dryades was the hub of what is now the Central City District, then home to many immigrant- and black-owned businesses. The library’s architect, William Burk, provided adult and children’s reading rooms on the building’s main floor and an ample lecture hall in the basement. Construction began in September 1914; the Dryades Branch was formally dedicated in October 1915. Its first librarian was Adelia N. Trent, who served until 1919.

For fifty years the Dryades Branch served its users well. Many community groups, for instance the Negro Board of Trade, the local chapter of the NAACP and Boy and Girl Scout groups, met regularly at the library. School children and adults enjoyed the library’s many services, programs and reading materials. Originally just 5,700 volumes, the branch’s collection would reach 13,000 by 1932 and include works by prominent African American writers. The library also established deposit stations in several of the district’s segregated public schools. Even after New Orleans desegregated its libraries in 1955, the Dryades Branch continued serving a predominantly African American clientele. It closed in September 1965 however, suffering damage from Hurricane Betsy. The building sat vacant for years until the Dryades (formerly Colored) YMCA acquired it for community programming. The New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission designated it in 1983. As of 2018, the building houses the James M. Singleton Charter School, part of the Orleans Parish School Board.

Sources: David M. Battles, The History of Public Library Access for African Americans in the South (Lanham, MD: Scraecrow, 2009); Shane C. Hand, “Developing Whiteness In the New Orleans Public Library, 1900-1930s,” Synergy 3:1 (Spring 2012); Cheryl Knott, Not Free, Not For All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow (Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

New Orleans Public Library

>History of the New Orleans Public Library

>Location Opening and Closing Dates

New Orleans Public Library City Archives and Special Collections

>Municipal Government Photograph Collection

>New Orleans Public Library Photographs

State Library of Louisiana

>Louisiana Historic Photograph Collection

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Savannah’s East Henry Street Carnegie Library (1914- )

The East Henry Street Carnegie Library is a branch of the Live Oak Public Libraries in Savannah, Georgia. It originally opened in 1914 as the Colored Carnegie Library, one of twelve segregated public libraries in the south funded by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie and one of the earliest African American public libraries in Georgia. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Though temporarily closed in the late 1990s, it reopened in 2006 after a major restoration and expansion project.

The opening of Savannah’s Colored Carnegie Library in 1914 was a major step for the city’s African Americans in their progress toward free library services. Their quest had begun ten years before, when the city established its first public library but prevented blacks from using it. As a result, the Colored Library Association of Savannah formed in 1906 and operated the Savannah Colored Public Library out of a doctor’s office on Hartridge Street. The Association’s twelve founding members included many of black Savannah’s professional, business, and cultural leaders. Although the library received an annual appropriation from the city, most of its collections were donations. But in 1909, after Andrew Carnegie offered the city $60,000 (later raised to $75,000) for a new main library on Bull Street, the Colored Library Association was encouraged to approach the philanthropist themselves. In August 1910, Carnegie offered them $12,000 for a small library. Savannah’s population at the time was 65,064, just under half of which were black. The Association used community donations to purchase a library site on East Henry Street, across from Dixon Park. Architect Julian de Bruyn Kops designed the building and local contractor D.P. Phillips built it.

The Colored Carnegie Library opened on August 14, 1914. Its inaugural librarian was Charles A.R. McDowell. Though its opening day collections consisted of only 3,000 volumes, the library immediately became an indispensable community institution among Savannah’s African Americans. It provided them with reading materials by black and white authors, programs to attend, clubs to join, and space for public meetings. While the library received support from the city, it remained supervised by a separate board until 1963, when Savannah desegregated its libraries. The Carnegie Library reopened as an integrated branch of the Savannah Public Library but continued to serve a predominantly African American clientele.

Over the following decades, the Carnegie library on East Henry Street fell into disrepair. Changes to building codes, including new ADA compliance standards, outmoded the building. By 2000, it was temporarily closed. In 2001, the Live Oak Public Libraries began raising funds to restore and reopen the library. It officially reopened in 2006. The restoration project won numerous architectural and historic preservation awards, including the Marguerite Williams Award from the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation as well as the National Preservation Award. An important part of Savannah’s African American history, the library’s former users include Savannah mayors Floyd Adams and Otis Johnson, former public school superintendent Virginia Edwards Maynor, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, and Pulitzer Prize winning author James Alan McPherson. An historical marker now stands outside the library building.

Sources: Margaret Walton Godley, Savannah Public Library History (Savannah, GA: Savannah Public Library, 1950); Cheryl Knott, Not Free, Not for All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015); Robert Burke Walker Jr., Georgia’s Carnegie Libraries: A Study of Their History, Their Existing Conditions and Conservation (University of Georgia: Master’s Thesis, 1994).

Related Archival and Special Collections:

Georgia Historical Society

>Digital Image Catalog

>Foltz Photography Studio Photographs

Live Oak Public Libraries

>Kaye Kole Genealogy and Local History Room (Bull Street Library)

>Carnegie Library (East Henry Street Branch)